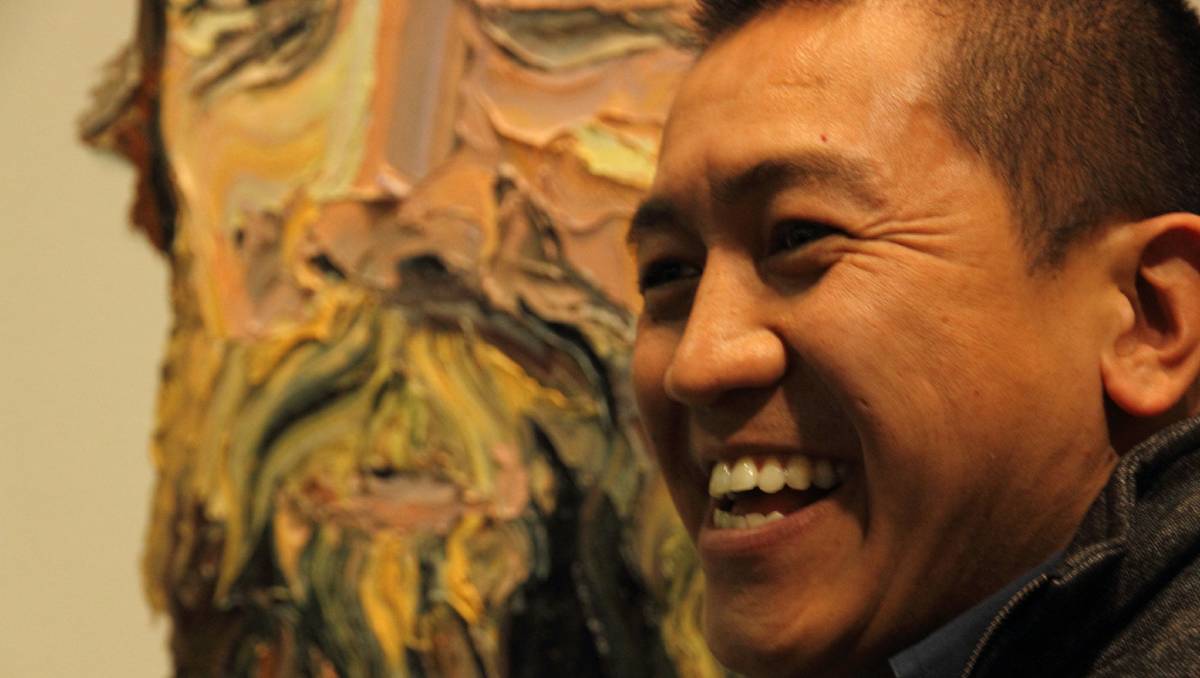

Anh Do has consistently appeared on lists of Australia’s most loved celebrities in the past few years while Kyle Sandilands has consistently appeared on lists of Australia’s most hated. The Vietnamese-born Australian comedian is adored for his stand-up comedy, TV appearances, and memoir The Happiest Refugee while Sandilands barely goes a week without some scandal on his top-rating radio show.

But that didn’t stop Do inviting the broadcaster onto his new ABC TV show Anh’s Brush With Fame in which Do interviews and paints the portraits of remarkable Australians.

“I don’t know where they do those ‘most-loved’ polls, but I’m not even the fifth-most loved person in my family,” Do says. “You’ve got to take all that stuff with a grain of salt.”

Do picked an eclectic bunch of guests for whom he either had great admiration or fascination. The full line-up is: Amanda Keller, Jimmy Barnes, Magda Szubanski, Craig McLachlan, Anthony Mundine, Kyle Sandilands, Kate Ceberano and Dr Charlie Teo.

“A guy like Kyle is a lot of things, but he’s never boring,” Do says.

Do was most interested to hear about Sandilands’ experiences growing up including the period in which the now super-rich radio host was homeless and living on the streets of Brisbane.

“He used to sleep behind a service station, and at night he’d listen to the radio that was coming through the bowsers. The voices of those radio announcers became his human company and that’s when he fell in love with radio.”

Do spent between two and four hours in the studio with each of the guests, painting their portraits while chatting and uncovering the experiences which made them the people they are today.

He uncovered some intriguing titbits: from an untold story of Barnes’s long-last daughter — which didn’t even make the final cut because, as Do says, you could do an entire series on Barnesy’s life — to Szubanski’s revelations about how her relationship with her father affects her life.

Do read Szubanski’s memoir, Reckoning, last year and decided immediately that she was his first priority as a guest. Not only is Szubanski — an Australian comedian who broke the mould — a personal hero to Do but they share similar experiences of fathers who were a part of violent and dangerous wars.

In addition to the interviews Anh’s Brush with Fame is very much a series about Do’s portraiture and his work in capturing the essence of these personalities.

In 2014 Do surprised Australia when his striking portrait of his father became a finalist for the Archibald Prize. Few of Do’s fans knew he had artistic talent though painting had long been one of his passions.

“Six years ago, a good mate of mine passed away at the age of 50, quite quickly. And it shocked me and made me think about all these things I want to do when I retire, like painting. And I thought: ‘If I put it off until when I retire, what if I don’t get there?’ ”

Do enrolled in a painting course at TAFE — where an 18-year-old fellow students asked if he was in fact that Anh Do, then refused to believe he was — and learnt valuable technical skills.

He’s painted many friends and family members, using cake spatulas to apply huge, dramatic smears to the canvas. Do says he usually chats with his subjects as he goes so it made sense to bring together interviews and painting.

“I paint really fast. I’ve just got a short attention span, and even if somebody said: ‘You’ve got five months’ I’d still probably finish a painting in a couple of hours because I don’t know how to paint slow.

“I grew up with old Chinese paintings on the walls at home, and the old Chinese or oriental masters, they would capture a boy sitting on a buffalo in a minimum amount of strokes. That’s not exactly what I’m going for, but I think that had an influence on how I wanted to paint.”

Do doesn’t allow his guests to see the progress of the painting until it’s absolutely finished so there’s a big reveal at the end of each half-hour episode.

But what did the famously forthright Sandilands think of his painting?

“I was worried what every guest would think, but with Kyle at least I know he’ll probably tell me what he really thinks,” Do says. “But you’ve got to watch it to find out. Telling you would be like giving away the price of the antiques on Antiques Roadshow.”